Estonia's central bank recently published a "revised overview" of the Estonian economy - with the intriguing title of "Estonia's economy on the way towards a more sustainable development path". At the same time the bank took the opportunity to cut its 2008 growth outlook in half, bringing its annual forecast down to 2% from an earlier 4.3% prediction. If this forecast proves accurate it will, as can be seen from the chart below, certainly involve a rather noticeable stench of burning rubber as the tyres screech to a halt.

"The long-awaited economic adjustment is under way in Estonia, but it is no longer as smooth as expected due to the less favourable external environment," the Estonian central bank said as it presented its lower forecasts.

This current 2 percent forecast compares with the 7.1 percent growth rate achieved in 2007 and the 11.2 percent one in 2006.

The bank also suggest that growth will pick up again to 3 percent in 2009, however, since we still don't really know how low the GDP growth number will - at the end of the day - fall in 2008 it is perhaps early days to start reaching any hard and fast conclusions on this front. In particular we still don't know whether or not we are going to see a hard landing in Estonia (or in the rest of the Baltics for that matter, or in Bulgaria, or in Romania) - and especially in the financial sectors in these economies - so until things are a bit clearer any hard-and-fast speculation about future growth and recovery paths is rather premature in my view, however happy it may make some full-time analysts to keep churning out the numbers regardless.

Returning for a moment to the growth numbers for Q4 2007, perhaps the most important detail to note is that annual growth for the quarter was still running at 4.8% while the seasonally adjusted estimate for quarter-on-quarter growth was only 0.8% - or an annual rate of 3.2%. These numbers - when they were first made public - were of course very low in the Estonian context, but now, given the sort of downward revisions we are seeing (the IMF also recently lowered their 2008 forecast to 3%, and of course there may well be more revisions still in the pipline), they seem quite the opposite. What I think we should thus be taking away with us here is the way in which trend has been showing a very steep and continuing fall over a number of quarters, and the decline has not come to a halt yet. When it does, then we will be in a much better position to start thinking in more detail about what a recovery might look like. For the moment perhaps our time would be better spent looking at just what downside risk we still have in the Estonian context.

The Outlook For Q1 2008

What is quite evident from the above chart is that growth momentum in Estonia has now been declining since the first quarter of 2006. What is also evident is that the loss of momentum is moving in fits and starts. Q3 2007, for example, shows a certain recovery from Q2, but then the decline continues in Q4. We will see moving forward if this "fits and starts" process continues. It wouldn't surprise me to see a Q1 2008 number which was slightly up on Q4 2007. But if it was - at say 1% quarter on quarter - that would mean we had effectively seen more than half the growth anticipated by the Estonian bank in just one quarter, which makes me want to ask myself some awkward questions concerning just what sort of growth we will then see over the rest of the year (ie, are we headed directly into recession in Q2?).

Alternately the downward drift might still continue in Q1 (hard to say looking at things like the industrial output numbers at this point) in which case the whole edifice would be well on its way down towards trawling the bottom.

Industrial output - according to the latest data release from the statistics office - was up in February, on both January (1.8%) and February 2007 (2.6%). This follows on the back of a revised 4.2% increase in January. Manufacturing output was also up, by 5.2% on February 2007, and by 2.4% (seasonally adjusted) on January. As can be seen in the chart below, December was very definitely a bad month, and even seems to have been an exception, so we now need to wait a little to see just where things move from here. Patience, I do believe, is most definitely a virtue in this type of situation.

EU Economic Sentiment Index

The EU Composite economic sentiment index for Estonia is also interesting, since while it shows a steady and constant decline from August 2006, since December 2007 it seems - for the moment - to have stabilised, a reading which is consistent with the idea that growth in Q1 2008 may not be dramatically down when compared with Q4 2007.

Inflation

Inflation - which has really been hitting the highs of late - was seen by the central bank as speeding up over whole year 2008 to 9.8 percent from 6.8 percent in 2007, and then falling back again to 3.0 percent by 2010. Estonia's inflation rate in fact fell back slightly in March from what had been virtually a 10-year high in February as the growth rate in food and housing costs eased back slightly. The annual rate dropped to 10.9 percent from 11.3 percent in February, according to data from the statistics office. Prices rose a monthly 0.8 percent.

Unemployment and Wage Inflation

Although the situation is far from dramatic at the present time, Estonian unemployment is ticking up steadily, and in March 2008 there were 17181 registered unemployed in Estonia - this was the ninth consecutive monthly increase - and unemployment was up 441 or by 2.6% from February. Nonetheless the unemployment rate remains extremely low at 2.7% according to recent data from the Estonian Labour Market Board.

So the labour market remains extremely tight, and as a result the adjustment process is very slow. Wages and salary increases peaked in Q2 2007 (see chart below) but they were still rising at an annual rate of 20.1% in the fourth quarter, and at an annual rate of 18.1% in December (which is the latest month for which we have data) or in real terms (subtracting the monthly 9.6% CPI inflation)by 8.5%, which is hardly the normal conditions for an economic slowdown and correction. We can reasonably draw the conclusion that this tight labour market and difficulty in getting wage inflation under control is going to make the correction a longer and more drawn out affair than it otherwise would be.

Exports

Estonia's trade deficit narrowed in January, reaching its lowest level in almost two years. A large part of the reduction was a result of a rapid drop in imports - which fell year on year by 4% in January, and this undoubtedly reflects the rapid contraction in internal consumer demand, but exports did also bounce back nicely, although the level of growth - at 4% - was still well below the 12% year on year growth rates achieved in October and November.

So while - looking at what has been happening in Germany and other CEE economies - we might reasonably expect that the uptick in exports may be sustained in February, the rather volatile nature of Estonian exports makes it hard to draw any worthwhile lasting conclusions at this point. We should however note that the improvement in the trade balance will impact positively on GDP, so this would argue in favour of a slight temporary improvement in growth in the first quarter.

The bank see Estonia's current account gap - which is one of the points most cited by ratings agencies as a key worry in terms of the overheating problem - falling to 7.5 percent of GDP by 2009 from 17.4 percent in 2007. The IMF currently forecast a CA deficit of 11.2% of GDP in 2008.

Meantime the slowdown is making itself felt on the Estonian government, which faces a revenue shortfall and needs to cut spending. Estonia must cut spending this year by 3 billion kroons ($303.4 million) to avoid a budget deficit this year, the central bank said. This fiscal tightening on the government's part will obviously be a negative as far as 2008 growth is concerned.

IMF Hard Landing Warning

However, if we look beyond the current quarter it is evident that things look rather bleak, and the risk of the slowdown becoming rather more disorderly is evident. Indeed, according to the the latest IMF Global Financial Stability report (published this week), a number of Eastern European countires now face a continuing and growing risk of having a "hard landing" as the global financial crisis continues to spread. The fund also drew attention to the possibility of serious of spillover problems arising for the Scandinavian, Italian and Austria banks that have lent heavily in the region, and this warning will not be taken lightly by these banks (whose benevolence and cooperation was, it will be remembered, thought to be the principal lifeline for the Baltic economies in times of distress).

At the heart of the IMF's concerns are the large current account deficits being run in certain CEE countries, deficits which have now reached extreme levels in some cases, running to the tune of 22.9pc in Latvia, 21.4pc in Bulgaria, 16.5pc in Serbia, 16pc in Estonia, 14.5pc in Romania and 13.3pc in Lithuania.

"Eastern Europe has a cluster of countries with current account deficits financed by private debt or portfolio flows, where domestic credit has grown rapidly. A global slowdown, or a sharp drop in capital flows to emerging markets, could force a painful adjustment,"

The IMF said lenders in Eastern Europe had built up "large negative net foreign positions" during the boom, especially in the Baltic states. "Liquidity for these banks has all but dried up and [interest] spreads have widened 500 basis points."

Many of these countries concerned rely on credit from branches of West European and Nordic banks, but these foreign lenders are now themselves having difficulty raising money in the wholesale capital markets.

"A soft landing for the Baltics and south-eastern Europe could be jeopardised if external financing conditions force parent banks to contract credit to the region. Swedish banks, the main suppliers of external funding to the Baltics, could come under pressure,"

One interesting indicator of potential risk for the financial sector comes from the inventory overhang in the property sector (see the chart below). Basically if important building and construction companies steadily accumulate unsold properties and then are forced into bankruptcy then the outstanding loans can all fall back into the banking system, causing all kinds of problems in the process.

As the IMF note in their report, awareness of higher risks in the CEE countries has been rising in recent months, and this rising awareness has been been reflected in the performance of bank stocks exposed to the region, in Credit Default Swap spreads, and in the performance of the Romanian leu (see chart below) given that the leu is the only floating currency with a liquid forward market among the group of eastern European countries with large external imbalances. As we have seen it has depreciated substantially since July 2007, as investors have been expressing their negative views on the region as whole The stocks of Swedish banks exposed to the Baltics have underperformed other Nordic bank shares (and here) partly owing to significant short-selling and CDS spreads on sovereign debt have surged since August 2007, as investor demand for credit protection has pushed up prices. The interesting point to observe is how this is now all moving in tandem.

Convergence and Growth

Finally, looking beyond immediate risks, it may also be useful at this point to consider some of the basic structural characteristics of the Estonian economy in the future. Now one of the underlying assumptions in the Estonia central bank forecast is that at some point Estonian domestic demand will recover in a fairly predictable manner. But there is no apriori reason why this need be the case. Part of the justification for the central bank view is what is known as "convergence theory". But in fact the evidence on convergence is quite contradictory, and really there are so many things we don't know and don't understand about the factors which condition economic growth that there are good reasons to be cautious here.

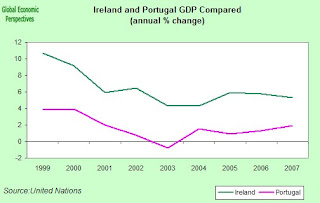

To give just one example I will take the cases of Ireland and Portugal. I do not do this randomly, since Ireland and Portugal form two quite contrasting cases, but then if we understood better why Ireland has been on one growth path while Portugal has followed quite a different one, then we would certainly be a lot wiser than we currently are. These two cases are interesting since both countries were founding members of the eurozone and both have experienced since the turn of the century one and the same monetary policy. Yet the results, as we can see in the charts below, have been very different. If we first look at the comparable growth rates the situation is clear enough.

While Ireland's growth rate dropped by from the very high levels of the late 1990s - which were never accompanied by the kind of inflation we are currently seeing in the Baltics - they comfortably settled into the 4% to 6% range, while Portugal's growth rate dropped steadily following the 2000 "correction" and has subsequently remained in the 1 to 2% range.

The result of this has been that Ireland's per capita income has first overtaken that of Portugal, and then soared way above it. If we look at the chart below, which is based on data prepared by Eurostat, we can look at the volume index of GDP per capita as expressed in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) (with the European Union - EU-27 - average set at 100). If the index of a country is higher than 100, then this country's level of GDP per head is higher than the EU average and vice versa. Basic data is expressed in PPS which then effectively becomes a common currency eliminating differences in price levels between countries and thus making possible meaningful volume comparisons of GDP between countries. Please note that the index, since it is calculated from PPS figures and expressed with respect to EU27 = 100, is valid for cross-country comparison purposes rather than for individual country inter-temporal comparisons. Nonetheless this chart is extraordinarily revealing, since it is quite clear that Irish and Portuguese GDPs per capita are far from converging.

Now if we start to think about the EU10, we could look at the case of Hungary. Hungary's domestic consumption as can be seen actually peaked in 2002., and since 2004 it has not be especially strong. It is now in full retreat. Would anyone like to tell me when it will recover, and by how much? I certainly can't tell you, but I certainly strongly doubt we will ever see the 2002 level again, and I am even rather unconvinced we will get back to the 2005 level. My intuition is that Hungary will now become an export driven economy.

And so we come to Estonia. As we can see domestic demand has been in massive retreat since the start of 2007. Will this recover, and by how much will it recover. The Bank of Estonia is reasonably happy to give an optimistic response. Personally I think there are good theoretical and empirical reasons for being rather more cautious at this point.

Finally, and at the risk of pushing my point just one bridge too far, I would like to take a quick look at German private consumption data. One of the core arguments I am presenting on this blog is the idea that part of the issue facing the Baltic economies is the population ageing one. This argument is being by and large ignored by mainstream analysts, but simply ignoring a problem doesn't make it go away. As we have seen from the Irish case, rapid economic growth is both possible and sustainable over long periods of time. But do the Baltic countries have the demographic profile to be able to follow the Irish path (and remember Ireland's growth has in part been possible as a result of migration there on the part of some - at least - Baltic citizens).

The Bank of Estonia, as I have been arguing, simply look at what is happening in Estonia on a "convergence" cyclical basis. But there are reasons for thinking that this view may be inadequate. Germany also had a very significant consumer boom and correction back in 1995, and if you look at the chart below German domestic consumption has never recovered.

And indeed if we look at the next chart we will see that in 2007 (following the significant VAT rise induced local spike in the 4th quarter of 2006) German private consumption has been steadily declining across 2007, and this despite a very rapid rate of new job creation and a substantial drop in unemployment. I think people should at least think about this carefully, and ask themselves whether or not Estonia may now follow this course, becoming an export driven economy. At least, I would argue, there are prima facie reasons for considering this outcome to be a real and present possibility.

Eesti Pank now estimate private consumption growth for 2009 at 3.8% and for 2010 at 4.5%. I think this view is unduly optimistic, and really puts the whole forecast in doubt. In the meantime we might perhaps like to ask ourselves whether Estonia's economy really is "on the way towards a more sustainable development path" or not. As I say, exports not domestic consumption are now likely to be the key, and with the inflation fire still burning away, and the rate of increase in global trade now slowing notably on the back of the credit crunch we may well ask whether the forecasted real (ie inflation adjusted) export growth of 4.8% for 2009 and 6.5% for 2010 are really all that realistic. It is one thing to pull numbers - like rabbits - out of a hat. It is quite another to make realistic forecasts.