Finland, we have recently been told, is the world's most prosperous nation, and it is deemed to be prosperous not only in monetary and financial terms, but also in terms of the implicit wealth of its democracy and governance. This striking assessment is to be found in the latest edition of what is known as the "Prosperity Index", an initiative launched by the Legatum Institute, a London-based think-tank. In fact Finland took first prize - up from third last year - and was closely followed by Switzerland and the other Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Denmark and Norway - also see Doug Muir's "debunk" of all this brouhaha here).

Finland was also notable for its recent second-place showing in the latest edition of the Tech-competitiveness index released by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The Index, which is commissioned by the Business Software Alliance, analyzes data on 66 countries around the world in an attempt to determine which of them have the most competitive information technology sectors. The study, now in its third year, examines variables like the overall business climate, the pervasiveness of the tech infrastructure, the strength and transparency of its legal system,and the availability of a well-educated and technologically literate workforce. As I say, Finland came in second to the United States, displacing last year's runner-up, Taiwan.

And if these accolades weren't enough already enough Finland this year took 6th place in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report (having been number one on earlier occasions). The Global Competitiveness Report purports to identify the world’s most competitive economies in terms of their prospects for economic growth.

Given all of this, you would really expect Finland to be doing pretty well during the current global recession, wouldn't you, what with all that fabulous prosperity and those stupendous growth prospects? So is it? Well unfortunately it isn't, indeed during the second quarter of 2009 Finland (which was way out in front of Ireland, another of those previous ECB "poster boys", which only managed to clock up a 7.4% annual contraction ) had the worst recession in the entire Eurozone, well behind the so called "PIGS" who everyone suspected previously suspected would be the ones to drag the common currency area to its downfall and ruin.

So in order to find out what is actually happening in Finland, and to take an inside look at the harsh reality that lies behind all those gleaming reports, let's take a leap across to the Finnish Statistics Office, just to see what is really going on right now in what some consider to be the world's most prosperous nation.

On our arrival we will calmly be told that, according to their latest revised data, the office found that GDP output (as measured by their ongoing working day adjusted index) fell in June by 8.9 per cent from June 2008. An 8.9% drop eh, that sounds pretty substantial, even to a hardened GDP watcher like me, accustomed to having my stomach turned by the latest releases to come from Ukraine and Latvia. So even if our Finnish were feeling pretty prosperous earlier this year, they would evidently seem to be feeling rather less so now. So why is this, and just what the hell is going on in Finland?

Sharp Drop In GDP Due To Export Dependence Vulnerability

Finland has in fact had the misfortune to fall into what is currently one of the deepest recessions to be found anywhere in the eurozone, a fact which I guess must strike some people as at least odd, given all the attention which people like me have been lavishing on those all too evident problems you can find in Spain or Southern Europe, or even Austria. But Finland, why is it that the deepest of deep recessions is to be found in Finland? This is the question I will try to answer in this brief report.

Steady Loss Of Competitiveness

To anticipate my findings rather, the culprit does seem to be, yet one more time, the poor old euro, since the availability of cheap finance and relatively easy and accessible growth markets during the years from 2000 to 2008 did see the country's industry steadily lose competitiveness and thus its quite large trade surplus, while membership of the monetary union today does mean there is no home currency left to devalue (and this is an important difference with Sweden) and this, of course, means that not only Ireland and Spain but even Finland will problably need a period of (in this case mildish) internal devaluation - rather similar perhaps to the one Germany went through from 1998 to 2005 - if it is to bring the ship right-side-up again. In the meantime, an early return to the country's former prosperity is not to be expected.

Sharp Fall In GDP In The First Half Of 2009

According to data from Eurostat, the Finnish economy shrank by a record 9.5 per cent in the second quarter when compared with the second quarter of 2008.

The drop represents the country's largest year on year decline in any single quarter since comparable figures first started to be compiled in 1990 and the fall is significantly worse than the 7.6 per cent year-on-year drop registered in the first three months of this year. Finland's economy contracted 2.6 percent in the second quarter of 2009 compared to the first quarter, when the economy shrank by a revised 3.0 percent over the last quarter of 2008.

Finland's economy is heavily export dependent and the country's key export markets - Russia and Germany in particular - have evidently been badly hit by the sharp reduction in the volume of world trade. In the second quarter, the volume of private consumption declined 3.4% on an annual basis, while investments decreased 11.7%. Exports fell by more than 30 percent and imports by some 28 percent on the year.

Seasonally adjusted GDP peaked during the first half of 2008, and has since fallen very sharply. In the first half of 2009, Finland’s economy contracted as strongly as it did at the start of the 1990s recession. At that time the biggest single drop occurred in the first quarter of 1991 (minus 2.7 per cent quarter on quarter). The biggest year-on-year drop in the 1990s was minus 8.0 per cent during the last quarter of 1991. So this is now more severe than the very severe early 1990s recession. In addition, as I have been suggesting, Finland’s economy is currently also contracting much faster than EU average. According to preliminary data compiled by Eurostat, in the second quarter of 2009 GDP in the EU area contracted by ony 0.2 per cent from the previous quarter and by 5.6% year on year.

Quarterly Contraction Slightly Slower in Q2

The economy shrank by a seasonally adjusted 2.6 percent in the second quarter over the first, compared with a revised figure of minus 3.0 for the equivalent first quarter drop, indicating the force of the recession only eased very slightly. Among European Union members, only the economies of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania saw deeper negative growth than Finland in the second quarter.

Explaining the decline in Finland, Pentti Forsman, an economist at Bank of Finland, said that exports now account for around 35 per cent of the Finnish economy from around half last year and the percentage will continue to fall into 2010. The problem is, it is very hard for Finnish domestic demand to take up the slack, given the age structure of the population.

Betweem April and June exports fell 30.2 per cent over the year earlier period, while investments dropped 11.7 per cent. Falling exports mean companies have been forced to cut jobs to adapt to their new output levels. In turn, rising unemployment means consumers are cutting back on spending - household consumption was down an annual 3.4 per cent in the second quarter.

Russia, Finlands top trading partner has also seen strong negative growth - around 10 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter.

Nokia has seen a quarter of its revenues wiped out, while paper producers Stora Enso and UPM-Kymmene are sharply cutting back production and jobs owing to the decline in worldwide newspaper sales and advertising revenue. Rautaruukki Oyj, Finland’s biggest producer of carbon steel, and Cargotec Oyj, the world’s biggest maker of container-lifting gear, have both suffered export-led losses. Cargotec said it expects sales to plunge 25 percent this year. And Konecranes Oyj, the world’s largest supplier of industrial cranes, is cutting production by as much as 30 percent and may close factories as miners, ports and manufacturers reduce spending on new material-handling gear.

Raw materials and capital goods account for about 80 percent of Finland’s exports while consumer goods and durables account for 12 percent of sales abroad.

Finland's finance ministry now expect the economy to shrink 6.0 percent this year before rebounding in 2010 with a 0.3 percent expansion - according to the latest forecast issued last week. Unemployment, could reach 9.0 percent this year and 10.5 percent in 2010 the forecast said.

The ministry said it expected the economy to pick up in conjunction with those of its biggest trading partners - Sweden, Germany and Russia - that is they do not anticipate an autonomous domestic recovery. But what will happen if the economies of those three countries are not on the road to recovery in quite the way the Finnish government expects?

"There are good grounds to expect that Finnish exports will strengthen in the latter half of the year," the government statement said.

And what if demand does not strengthen sufficiently to pull the national economic cart out of the mud tip which it is mired in?

Exports accounted for 47 percent of gross domestic product last year. They have currently dropped back to around 35 percent. And indeed the Finance Ministry now expects exports to sink to around 22 percent of GDP this year, downgrading a forecast of 18 percent from June, but grow again by 1.8 percent next year.

Not surprisingly the finance ministry warned that the much needed stimulus spending would weigh heavily on government finances - with the general government deficit-to-GDP ratio next year to breach the 3 percent EU stability and growth pact limit for the first time.

Finland has enjoyed public finance surpluses seen since 1998 but these will turn into a sizeable deficit this year (4.6% well over the 3% of GDP which is theoretically permitted) and we will more than likely see an even bigger one - 6.1 % according to forecasts - in 2010 As a result Finland’s gross government debt will be up by almost 50 percent next year, hitting 43.9 percent of gross domestic product in 2010 from 29.4 percent last year. While debt to GDP will still be comparatively low, the rapidly rising costs associated the very rapid ageing which Finland's population will now undergo means that the room for manouevre is less than it seems.

Sharp Output Falls All Round

The economic decline has been noted in all sectors, although manufacturing and investment have seen much sharper declines that private consumption. The drop in construction activity has been sharp, and output fell by 19.2 per cent in the second quarter of 2009 when compared with the corresponding quarter in 2008. The situation has improved somewhat and by July construction output was only down by 13.1 per cent from the previous year. The contraction was largest in the construction of buildings where turnover fell by an annual 16.8 per cent in July.

New building permits are also down, and in August were 25% below the level of a year earlier. And this is not the complete extent of the fall, since as can be seen in the chart these peaked towards the end of 2007. Indeed the level of new building activity would seem destined to fall quite substantially yet awhile.

House prices are down, but not massively to date. In the second quarter of 2009, the prices of dwellings in new blocks of flats and terraced houses fell by 1.0 per cent from the previous quarter across the whole country. In Greater Helsinki prices went up by 1.6 per cent, meanwhile in the rest of Finland prices went down by 2.4 per cent. The average price per square metre of new dwellings was EUR 2,738 in the whole country, EUR 3,525 in Greater Helsinki and EUR 2,454 in the rest of Finland.

From previous year the prices in new blocks of flats and terraced houses went down by 4.5 per cent. In Greater Helsinki the prices went down by 0.7 per cent and in the rest of country 6.5 per cent. According to the statistics office the data are based on the price information from the largest building contractors and estate agents, and as we have seen in Spain these are not always the most reliable sources for such information. Certainly the earlier rise in prices has been impressive.

And it is not only the construction industry, since manufacturing is also sharply down, and was 30.1 per cent lower in the second quarter of the year than in the corresponding quarter of the year before. Domestic sales contracted by 27.8 per cent and export turnover by 32.0 per cent from one year earlier. The decline was steepest in the chemical (-36.4%) and metal (-33.4%) industries.

Services have also taken a big hit, and total turnover in service industries fell by 7.4 per cent in the April to June period of 2009 when compared with the respective three-month period of the year before. Turnover in transport and storage fell by 17.7 per cent, reflecting to some extent the impact of the decline in Russian economic activity.

Retail sales are also down, but only moderately so. In retail trade, sales in January-August diminished by 2.5 per cent. Over the same time period, motor vehicle sales were 32.9 per cent and wholesale trade sales 19.8 per cent down on the year before. In total trade sales fell by 17.2 per cent in January-August. However, the deterioration does seem to be accelerating, since according to Statistics Finland, for August alone retail trade sales fell by 3.4 per cent from August 2008. Wholesale trade sales fell by 21.3 per cent and motor vehicle sales by 40.6 per cent.

Exports Are The Big Drag On The Economy

But it is the export sector that the pain is really being felt. Between April and June, the volume of exports shrank by 30.2 per cent when compared with the same period in 2008, although they only fell by 0.7 per cent compared with the previous quarter. Exports of goods decreased by 31.7 per cent and those of services by 24.7 per cent year-on-year. The volume of imports fell by an annual 27.7 per cent and by 6 per cent from the previous quarter. Imports of goods were down 31.9 per cent and those of services by 14.3 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter.

Unemployment has risen, but not drastically so. So the government stimulus programme is working to this extent. According the the latest labour force survey employment was down by 75,000 in September over September 2008. There were 192,000 unemployed persons in September 2009, i.e. 34,000 more than in September 2008. This meant that at the end of the third quarter the unemployment was 7.5 per cent, up 2.0 percentage points from the same time last year, but down slightly from the level in June and July.

But uncertainty over the pace of economic turnaround has increased, and the government expects unemployment to rise to 10.5 percent next year.

Deflation Not Inflation The Issue

The year-on-year change in consumer prices as calculated by the Statistics Finland methodology fell to -1 per cent in September. In August it was -0.7 per cent. In September, consumer prices were largely brought into negative territory by ongoing reductions in interest rates - the Finnish donestic CPI uses a different methodology from the EU Harmonised one, and captures changes in housing costs to some extent, a feature which arguably means it better captures the ongoing impact of the global financial crisis on living standards and household expenditure . Falling prices of liquid fuels, telephone calls, owner-occupied dwellings and real estate, and used passenger cars also lowered inflation. In contrast, consumer prices were pushed up most by year-on-year increases in rents, restaurant and café prices, food prices, retail prices of alcoholic beverages and tobacco.

In fact the deflationary trend is still not clear, since between August and September, consumer prices went up by 0.2 per cent, primarily due to increases in the prices of clothing. And indeed, using the EU Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices, the rate of inflation for Finland was still running at an annual 1.1 per cent in September.

Producer prices and naturally falling, and those for manufactured products fell by an annual 8.6 per cent in August. Export prices were down by 9.6 per cent and import prices by 10.7 per cent from August 2008 . The basic price index for domestic supply fell by 8.7 per cent over the year. The year-on-year change in the wholesale price index was -9.5 per cent.

The main reasons for the drop in producer prices was obviously the reduction in the price of oil products and metals, but again between July and August producer prices for manufactured products rose by 0.7 per cent. The rise in the prices came especially from increased prices of oil products, with the monthly rise in prices restrained somewhat by reductions in the price of paper and paper board. But all of this begs one important question - would price deflation in Finland be a good or a bad thing? Evidently Europe's monetary authorities are divided on just this question. For output to recover from the global financial shock mild inflation is certainly much better than mild deflation, but what about Finland's competitiveness issue? Finland needs some sort of price correction, to get back onto a positive export path, even if not of the order of the one which is needed in Spain and Ireland. This is the big disadvantage of sharing a common currency and not having one of your own to devalue. But clearly ongoing deflation will only weaken domestic consumption (as people put off purchase decisions into the future) and will compound any indebtedness problems there may be in the private sector.

It's The Difference That Matters

This post really needs to be taken in comparison with my recent piece on Sweden, since for some time now I have been scratching my head trying to see just what could be learnt from making a comparison between Finland and Sweden. Some of the differences are obvious - one is in the euro, and the other isn’t, once can adjust monetary policy and currency values, and the other can’t. Others are less so. Finland’s goods trade surplus has been declining steadily since joining EMU while Sweden’s has remained relatively constant. And Swedish males live on average three years longer than their Finnish counterparts. So what is important here, and why? And if convergence theory has anything positive to be said for it, shouldn’t we be able to observe so sort of convergence going on here.

First, and just to remind ourselves, here is the chart from Claus Vistesen which shows what the relation between population ageing and current account balance might look like. The key point is that as populations age beyond a certain point, a tendency to run a current account surplus emerges, as domestic demand steadily weakens, and becomes insufficient to drive growth. Evidence for this phenomenon can be found in Germany, Japan and Sweden.

The idea is that as median population age rises the current account dynamics of a country change. The last ageing phase shown to the right of the diagram is purely speculative at this point, although theory suggests that if the underlying momentum of ageing is left unaddressed it may well be what happens. But it is a development which is to be strongly avoided since although we do not yet know what happens when a society starts to dis-save at an advanced median age, the longer we can put off finding out, the better.

Which is why looking at Finland is important, since unlike the three aforementioned “ideal type” agers, Finland has in fact seen a deterioration in its external position over the last decade, and even though it has, up to now, remained a surplus country, the trend is certainly towards deficit, and this trend needs to be halted and reversed. Indeed this is the most pressing policy problem facing the Finnish authorities during the current recession.

Now let’s look at Finland. Once more the mid 1990s “transition” is clear. Finland moves from deficit to surplus. But unlike the Swedish case the surplus peaks around the turn of the century, and since then has been steadily weakening.

There can be a number of explanations for this. The pattern of ageing could, for example, be different in Finland. Or the euro might be a factor, with the loss of control over monetary policy leading to a steady deterioration in the level of international competitiveness. As we will see below, some part of the explanation may be provided by each of these, but first, lets take a look as some of the empirical aspects of Finland’s present recession, since it is evident that Finland, like many other countries, has entered a strong recession on the current back the global crisis.

According to the Bank of Finland, the current account balance stood at 444 million euros in July, slightly up from the June surplus of 442 million euros. This compares with a surplus of 585 million euros in July 2008. The July current account surplus was driven by the service trade balance, which converted a June deficit of 43 million euros into a surplus of 48 million euros in July. The income surplus stood at 258 million euros in July, up from 145 million euros in June.The goods trade surplus, on the other hand, contracted to 260 million euros in July from 429 million euros in the previous month, while the deficit in current transfers widened to 122 million euros from 89 million euros in June.

As mentioned previously, the goods trade balance has been deteriorating, and the earlier positive balance now needs to be restored.

Finland’s economy faces important challanges in both the short and long terms. Finland’s state debt is low at the present time, which gives the capacity for short term stimulus and bank bailouts. But it is rising, and reached a record high of 70.6 billion euros by the end of the first quarter of 2009. General government debt, calculated according to Eurostat methodology, grew by 7.5 billion euros in January-March, and reached 38 percent of 2008 gross domestic product (GDP). Still, there is plenty of stimulus ammunition left, the important thing is to use it wisely, and try to engineer an economic transition.

Overall, the government has pledged about €60 billion in guarantees, loans and investments, and is expecting a boost of €45 billion in corporate financing. Prime Minister Vanhanen described the decisions as ‘massive, even gigantic’. The largest sums of money are in the bank support package, which aims to secure the continuity of corporate credit. In fact, the Finnish parliament has already approved guarantees of €40 billion to help banks to raise capital.

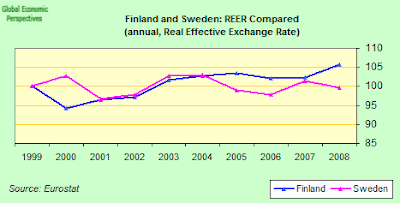

But in the longer term the issues raised in the course of this post need to be addressed. Competitiveness needs to be restored to the Finnish economy, and exports boosted, as illustrated by the REER chart below. In particular the situation pre 2007 needs to be restored. The change is not massive (maybe only 5% or so), so it is doable, and it needs to be done, especially since the Swedish Krona has been significantly devalued.

One of the things that stands out is Finland’s differential preformance vis a vis Sweden. Using data prepared by Eurostat which shows the volume indexes of GDP per capita as expressed in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) (with the European Union - EU-27 - average set at 100) it is apparent that a gap exists (see below) and that it is not being closed. In fact, after 1998 the two lines move tantalisingly in tandem, but with Finnish per capital GDP stuck just short of the Swedish level. Any reading on these indexes of over 100 implies that the country’s level of GDP per head is higher than the EU average and vice versa, and relative movements in the indexes imply that the rates of change in GDP per capita are either improving more or less rapidly than the EU average. The basic data behind the charts is expressed in PPS which effectively become a common currency eliminating differences in price levels between countries making possible meaningful volume comparisons of relative GDP per capita. Since the index is calculated using PPS figures and expressed with respect to EU27 = 100, it is only valid for cross-country comparison purposes and not for individual country inter-temporal comparisons, nonetheless charts based on such data are extraordinarily revealing.

And what of all those prosperity and competitiveness indexes we started with. Clearly they have been missing something here. A focus on institutional quality is fine, and I have nothing against it, but there is surely more to economic growth processes than simply having sound and effective institutions. Other forces are at work, and one of these is our demography, and as we can see in the Finnish case, simply leaving these out of our analysis won't help us avoid the problems that excessively rapid ageing presents for our economic system. I wish it would.