The Latvian government is getting nervous about the level of lending coming from Swedish banks. According to the Financial Times, "Latvia’s prime minister has warned Swedish banks they risk choking off recovery in the Baltic state’s crisis-hit economy unless they resume lending". The Latvian authorities are complaining, it seems, that banks such as Swedbank and SEB, which dominate the Latvian market, have reined in credit as they struggle to contain rising bad loans amid the deepest recession in the European Union.

“The . . . abrupt stopping of credit is a very problematic issue,” said Valdis Dombrovskis, the prime minister. “We expect Swedish banks to start [lending] again. “Of course you can say that Latvians were borrowing irresponsibly but to borrow irresponsibly you need someone to lend irresponsibly,” he said. “We had very easy credit in a very overheated economy. Now we have almost no credit in a very deep recession.”Well, here is some of the background. After an extended period when private credit was rising at nearly 60% a year, the Latvian credit bubble suddenly burst, with very unpleasant consequences for everyone. Since mid 2007 the annual rate of new credit has been falling rapidly, and turned negative in June this year. In fact total credit has been falling since October 2008.

Lending to households alone has also fallen back, after shooting up dramatically over several years.

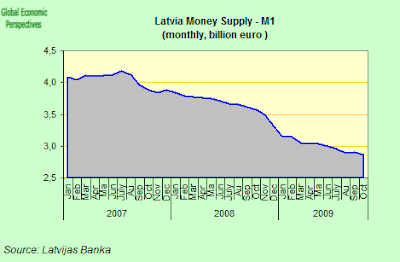

Lending to households alone has also fallen back, after shooting up dramatically over several years. And Latvian base money (M1) has also been falling.

And Latvian base money (M1) has also been falling.

In fact, and unsurprisingly (given that it is what we are seeing everywhere in the exploded bubble economies) the only sector which isn't deleveraging at this point is the government one.

So it seems hard to me to simply blame mean banks for not doing enough about a situation which many saw coming, but few were willing to do anything to avoid. Sure, the banks made a lot of bad decisions, but so did many other people, and each and every party is trying to extricate themselves from the mess as best they cab. In fact total Latvia debt is not in fact falling at this point in time, since while many individual Latvians have been frantically deleveraging, the government has been borrowing at a faster rate than ever, in part to bail out Parex bank, and in part to fund the ongoing fiscal deficit. In the meantime Latvian GDP has dropped sharply, falling back again in the third quarter at an even faster rate than in the second one. Which means that despite the fact that private indebtedness is falling, the level of private debt to GDP is still probably rising. This unfortunate situation is only further reinforced by the fact that prices are falling - not too fast as yet, only an annual 1.4% in November, but they are falling, and they will fall further, and this means that the percentage of debt to GDP will again rise, and this is especially bad news for the Latvian government (even though the drop in prices is a desired objective, no win-win strategy left to use now) since any fall beyond that anticipated is likely to push up the total debt level of 60.4% of GDP currently being forecast by the EU Commission for 2011.

This unfortunate situation is only further reinforced by the fact that prices are falling - not too fast as yet, only an annual 1.4% in November, but they are falling, and they will fall further, and this means that the percentage of debt to GDP will again rise, and this is especially bad news for the Latvian government (even though the drop in prices is a desired objective, no win-win strategy left to use now) since any fall beyond that anticipated is likely to push up the total debt level of 60.4% of GDP currently being forecast by the EU Commission for 2011.

And the pain doesn't stop, since having cut 500 million lati ($1 billion) in spending in its 2009 supplementary budget, the government initially resisted the idea of finding an additional 500 million lati of savings in the 2010 budget arguing that with no policy change the deficit was expected to be lower than the 8.5 percent target. Valdis Dombrovskis said in October his government could cut only 325 million lati in the 2010 budget and still meet the 8.5 percent target agreed with international lenders. The lenders did not agree, and Swedish Premier Fredrik Reinfeldt even intervened to tell Latvia it “must correct” its deficit. Following the rebuke further measures were passed equal to 500 million lati for 2010, and the country now targets a deficit of 7.6 percent of GDP. This is to be followed by a budget deficit target of 6 percent of gross domestic product in 2011, in order to finally arrive at the magic number of 3 percent deficit in 2012.

But considerable doubt exists over the ability of the Latvian authorities to fulfil these objectives. Which is why Mark Griffiths, IMF mission head in Latvia, describes the situation facing the government as challenging, and why the EU Commission base their Autumn forecasts on much higher deficit levels. The problem is that with domestic prive deflation (which is, remember, what Latvia is aiming for, the so called "internal devaluation" what is called nominal GDP (that is current price, unadjusted GDP) is likely to fall faster that the so called "real" GDP (adjusted for inflation) and this has two very undersireable consequences. In the first place debt to GDP goes up even faster, and the revenue which government receives (which is based on actual prices) drops faster than GDP, causing more instability in public finances. The deflator has shown falling prices since early this year and the EU commission is forecasting a drop of 5% for 2010.

So basically, in this climate, with unemployment rising, and wages falling, and an economy contracting at nearly 20% a year, it isn't hard to understand why not that much new bank lending is going on. Those who are creditworthy are trying hard to save, while those who need to borrow normally aren't that creditworthy, so Dombrovskis' plea is rather like asking the bank to subsidise new bad debts, and that is really not something you can do, and especially not when you are going along the course you are following because you wanted to, and against one hell of a lot of external advice. What kicked the whole process off was a short sharp credit crunch, but now it is the contraction in the real economy which is following its own dynamic, till someone finds a way to put a stop to it. It is the drop in output that is preventing banks from lending, and not banks being unwilling to lend that is causing the contraction to continue.

But there is another point in the FT article which should give food for thought.

Mr Dombrovskis...ruled out devaluation of the lat. While breaking the currency’s fixed exchange rate with the euro would help Latvia’s exporters, it would increase the burden of euro-denominated loans, which account for 85 per cent of lending, he said.

“We would not see much benefit from devaluation because we are a very small and open economy which means that any competitiveness gains we may get would be very short-lived,” he said. “We would redistribute wealth from pretty much all the population to a few exporters.”

Well, we haven't advanced too far in all these months, now have we, if we are still wheeling out the argument that "external" devaluation will hit holders of euro denominated loans, since it should be generally recognised that the (very painful) internal devaluation which is now taking place is hitting Euro loan and Lati loan holders alike. And the argument is a strange one to use just shortly after the statistics office announced that due to the rapid reduction in the number of those employed and to the fact that many of them changed their working conditions from full-time to part-time, the number of hours worked in the 3rd quarter of 2009 fell by an annual 27.3%, while labour costs fell during the same time period by 30.1%. This fall in disposable income, and the continuing prolongation thereof, poses a far greater threat to the continuity of Latvian loan payments than the 15% reduction in the value of the Lat as compared to the Euro which the IMF proposed in the autum of last year would have done. Indeed, it is, in and of itself, one of the pernicious consequences of having resigned yourself to an "L" shape non-recovery. Stress on the banking system only goes up and up, as incomes and employment fall, and the government has less and less ammunition left to counteract the contractionary pressure.

It is like sitting it out in freezing weather at the North Pole, in the vain hope that help will arrive. But help will not arrive, and the cruel truth about the post-crisis shock world we live in, is that nobody is coming to help you if you will not help yourself. In this sense, what Latvia doesn't need is more international borrowing (hasn't there been enough of that already) but some kind of meaningful strategy to start paying back the debt. But this means putting people back to work, and selling abroad, and financing Latvian lending from Latvian savings, and not pleading for yet more capital inflows to finance non-productive activities (attracting investment would be another matter, but as things stand right now the environment is far from "appetising", and according to the latest data from the Statistics Office, non-financial investment in Latvia was only 402.8 mln lats in the third quarter, a fall of 39% on the 3rd quarter of 2008).

And just to be clear, what we have seen to date is not a 30% drop in unit labour costs (which would, of course, mean a great boost to competitiveness), rather it is a drop in earnings due to the fact that the output people could have produced just isn't needed, since no one is willing and able to buy it. In fact according to the data of the Statistics Office to hourly labour costs fell by only 3.9% in the 3rd quarter when compared with the same period a year earlier. Hardly a massive drop, and especially not when the large annual increases of ealier quarters are taken into account (see chart below). The internal devaluation has a long course still to run!

Pensions Dilemma

But Latvia is back in the news today for more reasons, since the constitutional court has just ruled against the government pension cuts, drawing a question mark over Latvia's ability to meet the terms of its international lending commitments.

"The decision to cut pensions violated the individual's right to social security and the principle of the rule of law," the court said in its judgement, which cannot be appealed. The pension cuts - in place since July - formed a vital part of the Latvian government's list of austerity measures, as it struggles comply with terms of the IMF-lead bailout, and the constitutional inability to implement them is another hammer blow against the credibility of the current Latvian administration.

According to the Baltic Course, Valdis Dombrovskis told Latvian State Radio that the Constitutional Court's ruling on pensions must be carried out, and not debated. I am sure this will really come as music to the ears of people in Brussels and Washington. Basically pension reform forms a key part of the mid term strategy for sustainability of Latvian finances, and without the ability of the Latvian government to carry these out, then frankly the coherence of the whole strategy falls apart. If the Latvian constitution does not permit pension changes, then the Latvian constitution has to be changed, and the only surprising thing is that all this wasn't forseen when the initial loan negotiations took place in late 2008. Basically, it is impossible for the EU Commission and the IMF to accept any other view, since if any state could ring fence a whole part of social provision before entering debt negotiations, then non of the structural reform programmes could possibly work. This may seem harsh, but it is the price you have to pay for becoming insolvent as a society. Latvia's problems are NOT short term liquidity ones, but problems of the sustainability of an entire economic and demographic model, and, as in the case of Greece, these problems will not be solved by two or three years of (rather painful) fiscal deficit cosmetics. Real changes need to be made, and especially in raising the long term growth potential of the country, and frankly it is these changes which we have yet to see evidence for.

The issue is not simply one of limping into the Euro in 2012, even if as Mark Griffiths, the IMF’s mission head in Latvia, said in Riga last week the Latvian government does face a lot of “hard work” in trimming the budget deficit enough to qualify for euro adoption, and how much more so if they cannot constitutionally implement the cuts they agree to.

“The key is meeting the deficit targets, and meeting the Maastricht criteria and euro adoption, that’s the path,” Griffiths said. “The government needs to work hard over the next year to find the measures which will deliver that adjustment to meet those targets. It’s going to be a challenging task.”Oh yes, and Latvia was also in the news yesterday for another reason, since Latvian stocks dropped the most among equity markets worldwide as small investors sold stocks before the government starts to tax investment gains. The OMX Riga Index fell as much as 4.3 percent to 271.55, its lowest intraday level since August 21. In dollar terms, the drop was the biggest among 90 benchmark indexes tracked by Bloomberg. The reason for the sell off was that Latvia’s 2010 budget includes measures which will impose taxes on dividends, gains from trading stocks and bonds and interest income. These measures were agreed to in order to ensure the continued transfer of the 7.5 billion-euro bailout from the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund.

Latvian investors have increasingly sold their holdings ahead of the Dec. 31 deadline. Dividends and interest income will be taxed at 10 percent, while tax on gains from trading stocks and bonds will be 15 percent.

As Unemployment Climbs, Latvians Start To Pack Their Bags

Finally one that wasn't in the news, but should have been, since while everyone knows that at 20.3% Latvia's unemployment is the highest in the European Union (see chart below), what they don't know is that more Latvian's than even are now being forced to leave their country in search of work.

According to a report by Oļegs Krasnopjorovs, economist with the Bank of Latvia, during the first half of 2009 8,300 Latvian residents left for Great Britain, a twofold increase over the year earlier period. 3,600 people emigrated to crisis-ridden Ireland in the first 11 months of 2009 - 3% more year-on-year. Among the new EU member states, Latvia has seen the sharpest increase in emigration to these two countries.

According to Krasnopjorovs, the data (which comes from the UK and Irish social security systems) confirm the trend identified by the Latvian Statistics Office, who examined data on long-term migration. In the first ten months of 2009, the number of long-term emigrants was 6,300, up 18% more year-on-year; moreover the steepest rise took place in the last few months, reaching a ten-year peak. For several years now the number of emigrants has exceeded that of immigrants in Latvia, with the exception of the second half of 2007 when a sharp rise in salaries and a steep drop in unemployment were fuelled by the credit and construction boom, leading to labour force shortages and the expectation that incomes would rise even further.

Exports Still The Key

The real problem here, of course, is that the Latvian economy remains mired in deep recession, and shows few signs of real recovery, something which is not surprising given that domestic consumption is in limbo land (where it is likely to stay), while the Prime Minister seems to attach little priority to boosting exports, and regaining competitiveness. Indeed, the contraction has rather gathered than lost momentum in recent months, and on a seasonally adjusted basis Latvian GDP fell another 4% between the second and third quarters of 2009. This was much faster than the 0.2% contraction between Q1 and Q2.

Year on year Latvian GDP fell by 19.0% in the third quarter.The decrease was largely due to a 28.7% drop in external trade (share in GDP 15.6%), a 18.2% one in transport and communications (12.5% GDP share), an 17.4% fall in manufacturing (10.2% GDP share, incredible) and by a 36% drop in construction (7.5% GDP share, not far below manufacturing).

Private final consumption fell by 28.1%. Government final consumption decreased by 12.4%, while expenditure on gross capital formation fell 39.4%. Goods exports (68.2% of total exports) fell by 11.7% and services exports by 20.5%. Goods imports (82.1 % of total imports) were down much more sharply - by 36.6% -and services imports by 29.1%. Which meant net trade was positive, otherwise the fall in GDP would have been greater, and nearer to the levels seen in domestic demand.

And entering the fourth quarter there were few signs of any real improvement. Retail sales fell in October by 1.3% from September (on a seasonally adjusted, constant price basis).

As compared to October 2008 sales were down by 29.1%. The drop was even larger in the non-food product group – 32.3%. According to Eurostat data, sales are now down nearly 35% from their April 2008 peak.

Industrial output, however, seems to be holding up a little better, and output has stabilised since the spring. The problem is that manufacturing industry is now such a small share in GDP that it will be hard to pull the entire economy on the basis of anything other than very strong rates of increase. Industrial production was up in October by 0.1% over September, marginal, but at least it wasn't a fall. Unfortunately most of the increase was in the energy sector, with electricity and gas up by 10.3%, mining and quarrying contracted, by 2.1% as did manufacturing, by 1.9%.

Compared to October 2008 industrial output was down by 13.5%, Output in manufacturing fell by 15.8%, in mining and quarrying by 11%, while in electricity and gas output was only down by 2%. Output is now down around 21% since the February 2008 peak.

There is one positive glimmer on the Latvian horizon at the present time, and that is, of course, exports which were up by more than 4.4% (or 31.7 mln lats) when compared with September.

As a result, the surplus in the current account of Latvia's balance of payments reached 10.1% of gross domestic product (or LVL 327.9 million) in the third quarter. The surplus is however rather smaller than in the second quarter, which was 14.2% of GDP.

With export growth exceeding that of imports, the combined goods and services balance was positive for the second consecutive quarter, standing at 0.3% of GDP (or LVL 11.2 million). This effect is more due to services than to goods exports, since the goods trade balance is still in deficit (see chart), so there is still a long road to travel.

The largest third quarter capital inflows registered under the capital and financial account were the result of government borrowing from the IMF-lead support programme. There was some new foreign direct investment in Latvian companies to the amount of LVL 370.2 million, which to some extent offset direct investment outflows. Net external debt shrank by LVL 0.5 billion in nominal terms, but due to the fall in GDP (as I explained earlier) the ratio of net external debt to GDP posted only a tiny drop, reaching 56.4%, and gross external debt to GDP (excluding foreign assets) was up, reaching 145.8%.

So, as I say, a start has been made, even if there is still a long, long road to travel. Internal devaluation is the chosen path of the Latvian people, the best thing I can suggest at this point is to get it moving in earnest (in fact there is some evidence from November producer prices that the rate of price fall is now accelerating), and that Latvia's leaders start to value what they have (that is, export potential) instead of dreaming of what they can no longer have (dynamic domestic consumption driving growth). Living in the past is never a good idea, not even in the sentimental moments of Yuletide. A Merry Xmas to you all!