"Hungary’s potential economic growth should be 2 percentage points over the corresponding EU figure in order to ensure convergence".Two contrasting pieces of news about Hungary's economic plight have caught my eye over the last week. In the first place, and in an evident sign of the times, retail sales reportedly fell at their fastest annual rate in over ten years in October, whilst secondly, and more surprisingly, I learnt that Hungary’s economic-sentiment index rose to its highest level since October last year, when the gale force wind sent by the fall of Lehman Brothers engulfed the country. How can this be, I thought? These two pieces of information would, at least on the surface, seem to be pretty contractictory, with the former suggesting the deepest recession in living memory is getting even worse, while the latter seems to add backing to government claims that the worst is now behind them.

Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai, speaking in London in October

Gloomy Days Ahead For Consumer Spending

Hungary’s retail sales dropped 0.6% month on month in October, just slightly more than they did in September (-0.5%). In fact Hungary’s retail sales have risen only twice in monthly terms over the past 12 months, and one of these months was June (+0.2%) when consumer anticipation of an impending 5% VAT hike drove large crowds into furniture and household electronics stores. Not unexpectedly this was followed by the July numbers, which saw the largest monthly drop in a decade (-2.3%).

But a glance at the chart below should also reveal that the decline in retail sales is now long term, and not just a product of the recent crisis. Sales peaked in mid 2006, and have since been falling steadily, and while the year-on-year drop was as large as 7.5% in October - another decade long negative record - in fact they are now down nearly 12% from the August 2006 peak, and there are no strong grounds for believing that this trend will now reverse. And the reasons are obvious, since in addition to shrinking personal income levels, and a tighter credit environment credit, Hungary's ageing and declining population is also increasingly acting as a damper on household consumption.

In fact the situation with vehicle and auto part sales (which are not included in Eurostat retail sales) is even worse than the above data indicate, since given that Hungary is in the midst of a fiscal crisis, there is no room for a cash for clunkers type programme, and sales volume fell an annual 40.1% in the ten months to October, with the decline in October alone being 50.5% (following a 52.3% annual drop in September).

And there is worse news to come for the car sector, since even though the government hiked both the excise tax on petrol and the rate of VAT to 25% from 20% in July, sending fuel prices up like never before, yet another excise tax increase is now on its way. The excise tax on fuel is set to go up as of 1 January 2010 driving the price of gasoline and diesel up by roughly HUF 11 and HUF 7 a litre, respectively. As VAT is levied also on the excise tax, the VAT burden will also increase even if the rate itself won't change.

Confidence Rises

On the other hand according to the GKI sentiment index, confidence is now back at its highest level since October last year, when the credit crisis engulfed the country. The rise follows widely publicised government forecasts that the economy is now heading out of its worst recession in 18 years. The GKI sentiment index rose to minus 25.4 in December from minus 27.5 in November and a record-low of minus 46.2 in April. Business confidence rose to minus 16.7 from minus 18.9 and consumer confidence increased to minus 50.1 from minus 51.9.

According to Finance Secretary of State Tamas Katona Hungary’s economic decline bottomed in the third quarter of 2009 and the rate of contraction should ease in the final three months of the year. Katona suggested the economy may shrink 5 percent in the fourth quarter after contracting 7.1 percent in July-September. The economy is likely to contract an annual 6.7 percent this year and 0.6 percent next year before a return to growth in 2011, according to government forecasts (the EU Commission forecast a 6.5% decline in 2009, and a 0.5% one in 2010, while the IMF are predicting a 6.7% drop this year followed by a 0.9% drop next year). In the short term therefore, all are agreed that the economy will keep contracting, even if the possibility of a quarter of positive growth (which would technically mean exiting recession as currently defined) is not excluded.

The real issue facing students of Hungarian economic growth is thus not 2009, but the extent of any rebound in 2010 and beyond. It is on this rebound, and the level of inflation associated with it, that the future Hungarian fiscal deficit numbers, and the even more critical debt to GDP numbers, sensitively depend. The EU Commission currently forecasts 3.1% growth in 2011, while the Hungarian Central Bank is forecasting 3.4% growth in 2011 (see chart below).

The question is, are these expectations for such a strong rebound in 2011 really realistic, and even more to the point, is there any evidence for Prime Minister Bajnai's claim that a large number of analysts share his governments view that Hungary’s long term GDP trend growth potential is around 4%. Or put another way is there evidence for support for such an optimistic view of Hungary's growth future beyond the limited circle of economists who promoted the reform manifestoes (like Oriens, CEMI etc) on which current government policy is based? Certainly I can say that this analyst doesn't share that view, and reading around I have difficulty identifying others who do. Even the reasonable and ever moderate Portfolio Hungary were moved to raise an eyebrow at this claim, saying they "read Bajnai’s statement with a measure of surprise, as GDP estimates for Hungary have been typically way below 4%". The most pessimistic forecast they had seen was below 2% (this would certainly be my view, possibly 1% trend growth would be realistic at this stage), and they stated they were unaware of any "serious estimates above the 3% mark".

What is so striking (and in my view so unrealistic) about the kind of rosy estimates which are being circulated (as illustrated in the Bank of Hungary forecast chart above), is that not only do the median estimates seem to assume a "V" shaped rebound, even the outer limit, worst case type scenarious are based on the idea of a fairly strong rebound, and almost no consideration is given to the possibility that this may not happen, and that the country may be stuck nearer to an "L" shaped non-rebound, where rates of contraction slow, and slow, but growth proves to be surprisingly elusive and hard to come by.

These issues are not new, and I have blogged about then before (in this post - Hungary's Trend Growth And Debt Sustainability - about the scenarios offered for debt repayment in a paper by Lajos Deli and Zsuzsa Mosolygó from the National Debt Agency). Despite protests to the contrary, and despite the IMF's argument that "In emerging market countries with debt overhangs, the “Keynesian” effect of fiscal adjustment is likely to be outweighed by “non-Keynesian” effects related to expectations and credibility" it is really all about growth, more growth, and only about growth.

Non-Keynesian effects have to do with the offsetting response of private saving to policy-related changes in public saving. In particular, if fiscal adjustment credibly signals improved public sector solvency, a fiscal contraction could turn out to be expansionary, as private consumption rises based on the view that future tax hikes will be smaller than previously envisaged.The simple issue is, if domestic demand is (for demographic reasons) not able to rebound as the IMF (and the signitaries of the very influential Oriens Report "Recovery, A Programme For Economic Revival In Hungary") imagine, then how is GDP growth going to be strong enough to reduce the weight of debt to GDP?

IMF - Hungary, Request for Stand-By Arrangement, November 4, 2008

As everyone recognises, if domestic demand remains weak, growth will critically depend on exports, but the export potential of the economy will depend on the pace of recovery elswhere in the EU, and on relative prices as expressed through the value of the HUF, but almost no serious consideration is being given to the possibility that either the HUF is overvalued compared to the need to export or that EU growth may also be weaker and harder to come by than most median forecasts are assuming.

And indeed things are worse than they seem at first sight, since Hungary (and Hungarians) are, by and large, not in debt in their own currency, so allowing excess inflation does not sweat down the debt, since it only make export prices less competitive, unless you devalue to compensate, in which case the relative value of the debt is unchanged. But if you refuse to devalue, then, quite simply, you get hoisted on your own petard, which is basically where Hungary is right now.

So, the real question, as ever, is where the ingredients for growth are going to come from. Remember, Hungary's population is now declining steadily.

and ageing

and the working age population is also irredeemably falling.

As I said about the retail sales data above, these have now been falling since mid 2006, so it is hard to believe that we are going to see any significant resurgence (taking retail sales as a proxy for private consumer demand), especially as it seems Hungarian's are not now borrowing to anything like the extent they were two or three years ago (see below), and that (for age related reasons it is unlikely the earlier pattern will return. So I will correct myself: it isn't all only about growth, it is all about how to get the exports which can produce the growth. Anyone not recognising that is living, quite simply, in cloud cuckoo land, and after 40 odd years of Stalinist surrealism one would have thought that Hungarians in general had had enough of all this. But perhaps not. Look at the confidence index, and at how many people are prepared to accept Bajnai's assertion that Hungarian trend growth is 4% per annum.

Where Is The Growth Going To Come From?

"Looking at the structure of the Hungarian economy I frankly have difficulty seeing where the growth is going to come from. Without a major devaluation (and even then given international circumstances) Hungary will have problems attracting FDI in even the reduced quanities it has been doing over the last five years. The domestically owned private sector has enormous problems and is tied closely to the level of state spending. The financial sector and business services suffers from international problems and it isn't as if Hungary's largest bank - OTP - doesn't have some fairly serious problems of its own tied up in Ukraine, Bulgaria etc. Agriculture and food processing? Well, perhaps - but that isn't in that great a state either."

"It is worth pointing out that except for a brief period at the end of the 1990s when privatization receipts and above trend economic growth eased the situation Hungary has had a long term problem with its external debt going back to 1978 that it has never really escaped from. Successive Hungarian governments have prioritised the precise payment of the debt and have refused to seek rescheduling or restructuring on the grounds that this would damage business confidence. One can actually read the history of economic policy prior to 2000 as being about securing Hungary's public financing needs given this policy choice, to the detriment of the needs of the real economy. I read the relaxation of budgetary discipline after 2000 (and especially post-2002) as being about the interaction of mounting frustration at low living standards among the population with the dynamic of party competition.""That having been said, if one looks at the long view it is difficult to believe seriously that Hungary's debt burden will ever be paid off. Given that servicing these debts will depress the level of economic growth, I think it really is time that the EU, IMF and the authorities in Budapest swallowed hard and accepted reality - a realistic debt consolidation/restructure that takes in both the public and private sector debt is a fundamental condition of stablizing the situation. This is what no-one wants to recognise."

Mark Pittaway, Senior Lecturer in European Studies, UK Open University

Hungary’s third-quarter GDP contracted by 7.1% year on year in the July-September period compared to the 7.5% fall in Q2 .Quarter on quarter the economy contracted by1.8%, the sixth quarter in a row that the economy has shown negative growth.

Quarter on quarter Hungary's export-driven economy shrank 1.8 percent following a revised 1.9 percent contraction in the second quarter. This was the sixth quarter in a row that GDP growth was negative. The rate of contraction is down considerably on the 2.6% rate of fall seen in the first quarter, but the velocity of contraction is still alarmingly high.

In fact domestic demand fell by 13.3% year on year in the third quarter (see chart below), so the fall in GDP would have been much larger if it had not been for the impact of net trade.

As can be seen in the above chart, since the last quarter of 2008 Hungary's net trade impact has been possitive, and imports have fallen dramatically faster than exports. And the effect continues, since the export-import gap rose again in October, to 9 percentage points from 5.9ppts in September, following the high of 13.5 ppts in July, by far the largest seen in recent years.

This impact is not, of course, based on a strong recovery in exports, but rather by the fact that imports fall even more than exports (on an annual basis). Basically, when there is a movement in the net trade balance caused by a drop in imports GDP falls more slowly (following a pattern we have already seen in Spain, Greece etc). In fact, for statistical reasons a fall in imports appears as an INCREASE in GDP because the net trade position improves. But unless this drop in imports is accompanied by a significant improvement in the competitiveness of domestic industry (and hence a trade surplus driven by exports) then all you have is economic stagnation and falling living standards, since, for example, house prices will continue to fall, and everyone will feel worse off. Unemployment will obviously also rise, as those involved in the retail sector selling the imports will lose their jobs. People working in the ports for domestic directed external trade trade ditto.

This is the whole argument for devaluation in these kind of circumstances (Greece, Spain, Latvia, Hungary etc), since the devaluation not only helps export industries, it also helps the domestic sector by making imports more expensive. Thus, if demand was there, then a fall in imports would be compensated by a rise in domestic supply, and your interpretation of the equation would not hold.

The whole problem, however, in the cases of the former current account deficit countries is that the internal demand is now longer there, since it was based on unsustainable borrowing in the first place, borrowing that appeared to be supported by rising property values or state guarantees (in the case of fiscal deficits) as collateral. The property prices are now falling, and the deficits are now being slashed back, and neither are going to rise back again anytime soon and therefore the kind of borrowing we saw before isn’t coming back again anytime soon. So the bottom line is there is a sharp fall in consumption, whatever the headline GDP number says.

In fact the causal mechanism is that the absence of capital inflows leads to a drop in consumption, which in turn means there are less imports. But my big point is that the accounting mechanism used to generate the GDP number (making Net Exports a positive input convention) masks to some extent the actual drop in living standards, since Net Exports was previously negative (and hence a drag on GDP), and the drop in domestic consumption and imports simply makes it less negative.

Of course, there are two ways to make imports less attractive, one is devaluation and the other is structural reform to make the domestic sector more competitive, and that is the Oriens/Bajnai approach, and there is little objection at all to much of what they propose, except that, as we are seeing in one country after another this procedure doesn't act quickly enough to undo the severe distortions that had been produced earlier, but then I doubt, from what they say, that the Oriens signitaries would accept that these distortions were as severe as I argue they are - just look, for example, at the drop in domestic consumtion - 13% - and this after three years of near economic stagnation. Hope against hope.

This having been said, exports, and the current account balance have been improving in recent months, although not by a long way fast enough to push the economy back up towards growth. Hungary posted another huge foreign trade surplus of EUR 471 million in October, according to the latest revised numbers released by the Central Statistics Office. October marks the ninth month in a row when Hungary posted a trade surplus in the EUR 320-550 million range.

Despite this significant improvement in the trade balance the Current Account only just managed to sneak into surplus in the second quarter, largely as a result of the very strong negative balance in the income account, which is a product of the very negative net investment position of the Hungarian economy (ie non Hungarians own a long more of Hungary than Hungarian's own of the rest of the world, and this creates a huge imbalance, and as Mark Pittaway says the bullet will have to be bitten - one way or another - about what to do about this at some point.

Despite this significant improvement in the trade balance the Current Account only just managed to sneak into surplus in the second quarter, largely as a result of the very strong negative balance in the income account, which is a product of the very negative net investment position of the Hungarian economy (ie non Hungarians own a long more of Hungary than Hungarian's own of the rest of the world, and this creates a huge imbalance, and as Mark Pittaway says the bullet will have to be bitten - one way or another - about what to do about this at some point.

In October, exports dropped 11.8% year on year (on a euro basis), while imports plunged by 20.8% year on year.

This gradual improvement in Hungarian exports has also lead to a modest recovery in the industrial sector, mainly due to stimulus-programme-induced stronger demand in western Europe. Industrial output fell 15.6 percent in the third quarter, down from a fall of 20.5 percent in the previous three months, while recent data showed output grew month on month for the second time in a row in October.

Against this background, weak exports, and domestic demand in full retreat it is not surprising that investment has been falling, and dropped 6.8% year on year in the third quarter. What these continuing declines in investment mean is that the level of investment is now at much lower levels than it once was - below the 2005 level according to the rough and ready index I prepared for the chart below.

What these continuing declines in investment mean is that the level of investment is now at much lower levels than it once was - below the 2005 level according to the rough and ready index I prepared for the chart below.

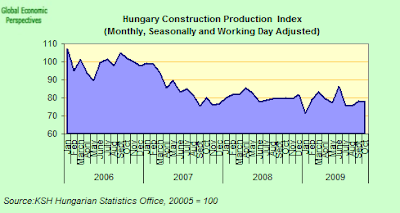

Construction activity is also well down, and has been for some long time now, following the sharp drop between summer 2006 and summer 2007 on the back of the first austerity programme (see chart).

Government consumption is also contracting due to the pressure to reduce the fiscal deficit.

All in all, the third quarter GDP data indicate that Hungary's domestic economy is not showing any signs of recovery whatsoever, nor should we expect it to do so. The hike in VAT in July hurt private consumption while capital spending has been continually cut back given the failure of export demand to rebound as strongly as hoped. The need to maintain a restrictive fiscal policy stance will also indirectly weigh on consumer and corporate spending, with the consequence that in my view GDP will decrease by nearly 7% in 2009 and then by around 1.5% in 2010.

Monetary Policy Tangle

Hungary's central bank (NBH) last week cut its base rate by 25 basis points to 6.25%. The move which suprised the market participants (the consensus had been for a 50-bp reduction in surveys conducted by both Portfolio.hu and Reuters) now means the benchmark rate has been cut by 3.25% since July. Not everyone was surprised however, since in an interview on 10 December, Centrak Bank MPC member Péter Bihari had said it would be wise to calm rate cut expectations. "Any overshoot in (rate cut) expectations can backfire later. We (the central bank) need to stay sober, and we also need to communicate this sobriety outside," he said.

Although Hungary’s inflation outlook might have justified a 50-bp cut, the recent weakening in the forint (the HUF hit a 6-week low vs. the EUR last week) and the rise in the 5-yr CDS spread to a 3-month may well have signalled the need for a more cautious move, since following events in Dubai and Greece questions are rising about how long the relatively favourable global investor mood can last. Also, the imminence of elections, and the dangers of fiscal loosening (either before or after the election) urge prudence, especially in the light of what we have just seen in Greece.

The smaller than expected move also suggests that easing will be cautious in the first months of next year, and that the bank will be sensitive to any signs of worsening market conditions (especially ahead of next spring’s elections). Weaknesses in the real economy still argue for lower rates, and without moving towards closing down the interest rate gap forint loans will never become competitive with Euro or CHF ones"

Despite this afternoon’s decision by the National Bank of Hungary (NBH) to cut interest rates by a smaller than expected 25bps to 6.25%, there is a good case for further monetary easing over the coming months. We continue to think that the profile for interest rates priced into the market is too high."

"Both we and the consensus had expected a larger 50bps cut today, although the fact that one member of the Council voted for a smaller 25bp reduction in November did suggest that a slowdown in the pace of easing was possible. The forint gained 0.25% against the euro immediately after the decision."

"Nonetheless, while policymakers may now move in smaller steps than we had previously thought, the case for further monetary easing remains strong. The decision to cut by just 25bps today is likely to have been motivated in part by signs that output in some sectors (notably industry) has started to pick up. But while the prospects for some parts of the economy have undoubtedly improved in recent months, the overall pace of recovery will remain subdued."

"In particular, domestic demand will remain a significant drag on growth. A combination of a fragile banking sector, a high proportion of fx-denominated debt and the continued rise in non-performing loans, means that the overall availability of credit remains constrained."

"And although the bulk of the tightening measures have now been implemented, a public sector wage freeze, and private sector wage restraint needed to offset the recent sharp rise in unit labour costs, means that the pain will linger into 2010 and 2011."

Neil Shearing, Capital Economics

Inflation Overshoots Expectations In November

Hungary’s consumer prices rose 5.2% year on year in November, an acceleration from the previous month (4.7%). Month on month prices were up 0.3% . This was an upside surprise since analysts forecasts had been for a rise of 5.0%.

The main reason for the increase was an increase in the prices of unprocessed food (especially fruits and vegetables), energy and fuel. Disinflation is slowing in tradable goods, driven mainly by the durable goods sector (especially new and used vehicles and televisions), while market services disinflation came to a halt (most service prices increased except for tourism and books).

The impression is that the underlying disinflation process has started to slow and there are risks to the medium term inflation outlook. The seasonally adjusted core inflation has been stagnant at around 5% since July, while the CPI adjusted for tax changes started to accelerate in November (it moderated from 3.7% YoY in June to 0.9% in October and picked up to 1.4% in November).

Which means the NBH’s inflation forecast of 1.9% for 2011 may come under pressure. Inflation may well accelerate to 5.6% in December and peak at around 5.8% in January and can then fall to below 3% by the end of 2010. As Neil Shearing says "Despite the uptick in inflation to 5.2% in November (from 4.7% in October), we support the Central Bank’s view that it will "significantly undershoot" the 3±1% target when July’s VAT hike drops out of the annual comparison." Still maintaining this sort of price range with the present Forint value is simply going to prolong and prolong the economic downturn.

Employment Falling As Unemployment Rises

Unsurprisingly, against this background unemployment is rising and rising, hitting 9.9% of the labour force in October, according to Eurostat seasonally adjusted data.

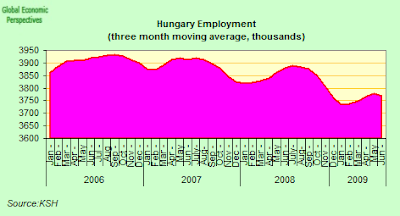

Total employment has been on a downward trend since the middle of 2006.

Total employment has been on a downward trend since the middle of 2006.

But one of the impacts of the economic crisis has been that employment in the public sector, after falling under the austerity programme has risen sharply since the spring (due to a number of employment schemes designed to keep unemployment down, especially in the regions), and is now back up above its earlier level.

Real ex-bonus wages (the central banks targeted measure of wage inflation) has been in negative territory (by around 1%) since the summer.

Real ex-bonus wages (the central banks targeted measure of wage inflation) has been in negative territory (by around 1%) since the summer.

Bank Credit Turning Negative

As is well known a very high proportion of mortgages in Hungary are non-forint denominated (over 85%, mainly in Swiss Francs), but the HUF value of these mortgages has been falling for over a year now.

As has the total value of outsanding mortgages in any currency.

As has the total value of outsanding mortgages in any currency. Although the stock of mortgages had not been high by some West European standards (around 50% of GDP), they had been growing at a rate of around 20% per annum over the last several years (see chart) but the crisis brought this to an end, and the year on year increase was down to only 2% by October, and will more than likely be negative by the end of the year. Which means, credit expansion and new house construction will NOT be driving any coming Hungarian recovery.

Although the stock of mortgages had not been high by some West European standards (around 50% of GDP), they had been growing at a rate of around 20% per annum over the last several years (see chart) but the crisis brought this to an end, and the year on year increase was down to only 2% by October, and will more than likely be negative by the end of the year. Which means, credit expansion and new house construction will NOT be driving any coming Hungarian recovery.

In the current climate, with unemployment rising, and wages falling, and an economy contracting at nearly 7% a year, it isn't hard to understand why not that much new bank lending is going on. Those who are creditworthy are trying hard to save, while those who need to borrow normally aren't that creditworthy, so pleading to the banks to lend more is rather like asking them to subsidise new bad debts, and that is really not something you can do. What kicked the whole current process off in Hungary was a short sharp credit crunch, but now it is the contraction in the real economy which is following its own dynamic, till someone finds a way to put a stop to it. It is the drop in output that is preventing banks from lending, and not banks being unwilling to lend that is causing the contraction to continue.

Election Chaos Looming

Having seen the shennanikins which have recently taken place in Greece, it was obvious that the run in to the coming election was always going to be complicated, with accusation and counter-accusation being thrown from one party to another. The big problem is that neither party has exactly clean hands in this context, but one thing seems sure, that the 2010 budget is liable to slippage, whether because of the current ruling party moving invoices from 2009 to 2010 (on the assumption that they are going to lose the election, so what the hell), or because the incoming party is going to make promises which will lead to an overspend which they will then blame on their predecessors.

A group of economists close to opposition party Fidesz now claim next year’s budget "is full of tricks", including unrealistic macroeconomic assumptions that will lead to a deficit far larger than the cabinet’s projection. The current Finance Ministry Péter Oszkó played down the criticism as politicking ahead of the coming elections, and this may well be, but some of the points they make to not, for all that, lack validity.

The 29 economists, who promoted a 'no’ vote on the 2010 budget bill in November, include Zsigmond Járai (Finance Minister of the Fidesz government and former Governor of the central bank), Ákos Péter Bod (Ministry of the Industry in the MDF cabinet and former Governor of the NBH), György Szapáry (former Deputy Governor of the NBH, currently responsible for international relations in Fidesz), Tamás Mellár (head of the statistics office (KSH) during the Fidesz government) and Károly Szász (head of financial markets watchdog (PSZÁF) in the Fidesz era).

Zsigmond Járai argues that, on the one hand the 2010 budget is based on unrealistic macroeconomic assumptions - e.g. only a 0.6% economic contraction while GDP may well shrink by considerably more, possibly by as much as 1.5%, while on the other planned austerity measures, like reduced subsidies, will also worsen the balance. Among his list of "overestimation tricks" the former central bank head mentioned VAT and corporate tax revenues. The economists claim that the underestimation of the GDP contraction will result in something like HUF 200 bn less budget revenues, adding that another HUF 200 bn shortfall due to smaller-than-expected revenues from taxes and contributions.

The current official estimate for the general government deficit in 2010 is 3.8% of GDP, a target which is considered to be realistic by both the IMF and the European Commission. The Fidesz economists claim the gap - without supplementary bufget changes - could be as high as 7-8% of GDP. György Matolcsy, a leading Fidesz economic spokesman stressed that such a large deficit would be unacceptable for Fidesz as well, and made clear that they are not saying such a massive budget overrun should be tolerated.

Matolcsy said the 2010 budget included no reforms or system overhauls to jumpstart growth in the second half of 2010 as the cabinet expects, and that in his opinion a sustainable growth path is unlikely to be reached before 2013.

The document has not been slow to attract criticism, and apart from Finance Minister Ozskó, Lajos Bokros, Hungary’s former Finance Minister and PM candidate from the minor opposition party MDF, lashed out at the group saying their argument was "ridiculous".

In an interview with public television MTV, Bokros said that "the only alternative to sovereign default was to cut budget spending, take away welfare contributions, e.g. the 13th-month pension and 13th-month wage in the public sector that spun the economy into catastrophe and that led to (government) debt to surge sky high." "How do you create growth from these (measures)? Only via reforms," he stressed.

A large part of the issue seems to revolve around what to do with the bulging debts of quasi governmental institutions like hospitals, the state-owned railway company MÁV and the Budapest Transport Company (BKV) . Fidesz seems to assume that these debts will need to be swallowed. Bokros does not agree: "If a budget were about consolidating the debts of every (state-owned) companies automatically and without restraint the next year, it would be but a rejection of any reform," he said. "Reforming" according to Bokros means not covering the debt of "inefficiently operating public institutions", because these liabilities had probably been accumulated due to their profligacy."So, what do you have to do then? [You need to implement] reforms and a create a competitive situation that will have inferior companies go bust and good-quality institutions double in size."

While sympathising with Bokros in the spirit, it is not clear to me that things are going to be so easy as he imagines in the letter. One thing is however clear, he is right that if solutions are not found for these issues, especially in the problematic pensions and health sectors, Hungary will go bankrupt.

One thing is clear though, life is not going to be easy in post election Hungary. If Fidesz is voted back to power it will create a new budget, a new tax regime and a new labour policy for as early as July, according to György Matolcsy, and the new government should also sign a new Stand-By Arrangement with the IMF. Matolcsy reiterated that Fidesz has three scenarios for the tax system: one proposing a radical reduction of personal income tax with a flat family rate; another which would decrease rates on the entire spectrum of taxes; and a third which would cut social-security and health-insurance contributions for employers and employees alike. The only thing which doesn't seem clear is how he expects to pay for all these, especially since he doesn't anticipate a serious return to growth before 2013.

Matolcsy also claims that the budget deficit will be 3-4 percentage points higher than the targeted 3.8% of GDP, citing central bank staff projections in their Inflation Report that the gap is likely to be 4.3% of GDP. Fidesz expects the gap to come in at 4.5% and foresees that state-owned enterprises such as the railway company would need debt consolidation amounting to 3% of GDP. Matolcsy also pointed out that there may be other downside risks to next year’s budget beyond the 7.5% deficit he claims it already incorporates, including a larger-than-expected contraction in consumption, unemployment and a fall in lending to households that could lead to smaller tax revenues. All of these points are not without some validity. Further the ongoing drop in investment will continue to eat into tax revenues and lower-than-forecast inflation could decrease budget income next year, he added.

Fidesz The Likely Winners, But By How Much?

The gap between Hungary’s two main political parties has narrowed slightly of late, according to the latest opinion survey by Medián. While an increasing number of voters reported a lack of strong party affiliation, Fidesz has witnessed some decrease in its supporter base. Support for Fidesz within eligible voters has been gradually melting away in recent months, and is now down to 40% in December from 43% in November and 47% in July. The Hungarian Socialist Party meanwhile saw a only a minor and not statistically significant increase in support. But this change in percentage support is more due to an increase in undecided voters than anything else, since 66 per cent of respondents — all decided voters — would vote for Fidesz in the next legislative election, up one point since October.

The ruling Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) remains a distant second with only 19 per cent, followed by the Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik) with 10 per cent. Support is much lower for the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), Politics Can Be Different (LMP), and the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ).

We should not forget that although Bajnai is portraying himself as being the head of a technocratic government, he is in reality the head of a government which is supported by MSZP. It is clear that the 2010 elections are lost. The game is already for 2014 elections. The government now have apparently stabilised the forint, slowed down the shrinking of the economy, and restored some kind of order and feeling of leadership. The price is high, but it seems that the population by and large accepted the situation as it is. The slight increase of popularity of MSZP and Bajnai himself may support this statement. Now, compromises have been made for a short time with major public service sector agents to accept the restrictions. But, somewhere around next August everyone will be up in arms for new financial support. The latest move of the government, to finally accept the long term and symbolic demand of FIDESZ to cut the VAT on the gas-price to 5% is already, I think, a mine for FIDESZ laid down to explode next year. All the messages of the members of the government are now portraying the government as a similar "responsible" stabilisation force as the 1995 Bokros package was, which would propel again Hungary into a "sustained" high growth as was experienced between 1997-2005 (of course now we all see better the price of this decade of growth). So what we are seeing here is a creation of a "new development" discourse, which it is expected will be destroyed by the "incompetence" etc of the Orban government. - Andras Toth, Sociologist

Huge Structural Reforms Gamble

Well, I think I have said more than enough already in this post, so I think I will leave your with the thoughts Gábor Egry (a Hungarian political scientist) expressed in an e-mail interview with me. Basically it seems to me that Gábor is right, the 4% growth target has no scientific basis behind it at all, and is just a hope that has been repeated so many time people now think it has become a reality. What is going on in Hungary now is a huge gamble, a leap into the dark almost, based on the idea that a shift in the tax structure, and a fiscal discipline to reassure would be investors can bring a growth surge, a growth surge which I argue is structurally impossible without doing something about the level fo the forint, the problem of the forex debt, and without getting domestic monetary policy firmly back in the hands of the NBH.

Gábor Egry - Research Fellow, Poltikatörténeti Intézet (Institute for Political

History)

Maybe it is worth taking a look at the history of this idea of 4% trend growth. As far as I can recall it - apart from the constant remarks of politicians that Hungary needs a growth 2 points higher than the EU core states and this was somehow always expected to be 4% - both before and after the last elections a group of economists started putting forward ideas for the renewal of sustainable growth in Hungary and they elaborated a series of - let's put it this way - Slovak-type measures would very soon result in 4% trend growth. As the then government chose another type of policy mix for their budget consodilation, these critics never failed to emphasize that with this Slovak-type set of measures not only would the slow growth period after the budget (austerity, 2006) restrictions have been avoidable, but that these Slovak measures were the only possible way to elevate the trend growth to 4%. Usually it was the same guys coming with the same proposals, just branded differently. (CEMI, Oriens etc). Then, when in 2008 the Reform Aliiance was formed, they recycled these ideas. And even though the Bajnai government is an MSZP supported one at least initially it was the result of Gyurcsány's attempt to compell the party to accept the Reform Alliance program. From this persepctive Bajnai's statement is quite logical: they are implementing measures that were proposed by experts with the promise that they would lead to a 4% trend growth. Anyway, the idea that such measures will restore a higher and sutainable trend growth is deeply anchored in the Hungarian economist's thinking, and most of them - among others Bajnai, who was the loyal but critical supporter of these ideas in the Gyurcsány government - will adhere to it as it was the main component of their criticism of earlier policy and as such it is a core component of their common identity.Beyond the historical anecdotes I see some serious faults and gaps in the reasoning behind the approach, especially as their reasoning is really causal, but rather based on the use of analogies. The main thrust of the approach is not simply to make production in Hungary wage-competitive by cutting the so called tax wedge, but also through making labor cheaper for local companies and attracting FDI, thus raising the employment rate. So, they work with both a direct causal relationship between tax rates and the employment rate and with an indirect one, but they then connect this second one causally to the tax rates again. I would argue, that such soft factors, as labour mobility have had at least as as important impact in the Hungarian case. According to Oriens, the FDI sector in Hungary is said to be overcapitalized, but I'm not sure whether this is because of the relatvely high labor costs or is a result of the immobility of the workforce. It is really important to observe how unemployment is geographically distributed in Hungary, and how this geographical distribution has not changed in the last two decades, despite efforts to change this situation with methods in principle similiar to the present ones, i.e. giving incentives indirectly through economic policy to market forces.

There really are areas where even near-starvation was not capable of moving people out of their villages and making them go look for employment elsewhere. I know that there are counter-examples in the sense that in huge areas a lot of people remained deliberately unemployed as they have found easier ways of making money in the grey or black economy, for example, near the Ukrainain border. Such people, instead of being moved by the modern dynamic of the market economy, resorted to - let's put it vaguely - pre-capitalist methods of work organization and resource redistribution. I don't really see how any kind of tax cuts will move them out from these places and as they have no significant taxable or taxed income it won't generate surplus demand for local companies either. Otherwise, I wouldn't neglect the fact that the fall of unemployment and the rise of employment in many Eastern countries coincided not only with lower taxes, but with EU accession, making it much easier for people to seek work in the West. And in fact millions did it. (For example at least 10% of the Slovak workforce worked abroad before the crisis.) But this is mobility is more or less lacking in Hungary, and Hungarians by and large never left for the West seeking work.

On the question of the deficit, it wouldn't surprise me if there was some accountancy massaging going on behind the scenes. The government may well have put a part of this years deficit on last year's one, raising that from 3,2 or 3,4% to 3,8 and they try to convince the state railways not to reclaim their VAT this year etc. Oszkó conveys self-assurance but he is paid for that. I wouldn't be surprised to find out at the end that this year deficit will be higher than forcast, but I don't see too much room for the IMF to protest, either.

They let Latvia raise its deficit a number of times, Romania is not only doing the same but may even finance the deficit (or in a more populist tone, this year's pensions) from IMF money and - at least as far as I can see - even accept political arguments regarding government incapability to implement unpoular measures before specific elections as arguments to support non compliance. Maybe Hungary will overshoot the deficit, but at least on the surface - in terms of measures implemeted - it is adhering to the terms. The government can simply tell them, ok, guys we did what you proposed, a slightly higher deficit was the result, accept it. Moreover, with the animal spirits currently prevailing around the world I really don't think the news of a 4,1% deficit will do any harm as long as markets are in love with recovery, while even a surplus can not prevent a collapse if their mood changes fundamentally...