I've been trying to draw attention to what is happening to Slovakian GDP for some months now, since I felt the consensus has been missing something (see this post, and this one). The Economist, for example, has been arguing some sort of version of Baltic and Hungarian exceptionalism in Eastern Europe, and even pointing to Slovakia as a positive example to be followed.

“Most other countries in the region are faring much better, though….Like Slovenia, which joined two years ago, Slovakia can enjoy the full protection of rich Europe’s currency union, rather than just the indirect benefit of being due to join it some day.”This example is far from isolated, yet, as I have already indicated in this post, the April EU sentiment indicator showed that business and consumer confidence in Slovakia was doing rather worse than the even that in the Baltics, so something relatively unpleasant was obviously happening.

And now we know for sure that it was, since according to last Friday's flash data release from the national stats office Slovakia's economy contracted by 5.4 percent year on year during the first three months of 2009. By way of comparison we could note that the economy expanded by 8.7 percent year on year in the first quarter of 2008. The latest results simply confirm what most Slovak economy watchers, the central bank, the European Commission and others already knew: the country is set to enter recession and remain there throughout 2009.

While the sharpness of the contraction in the first three months is pretty eyebrow raising, it does not come as a total shock, since in its revised GDP estimate released on April 7, the National Bank of Slovakia had already forecast that Slovakia’s economy would contract by 2.4 percent over the course of 2009. At the end of 2008 the bank was projecting growth of 2.1 percent for 2009, so the turnround is pretty sharp. And while the local stats office haven't yet given us a seasonally adjusted quarterly figure for the contraction, last Friday's Eurostat EU GDP release gave the figure of 11.2% for Slovakia q-o-q (which may well not be seasonally corrected, so I am evidently not suggesting they were dropping at a 44.8% rate in the quarter, which would obviously be ridiculous).

Total employment is also also down, falling in the first quarter of 2009 by 0.4 percent year-on-year, so that at the end of March there were 2,199,900 persons employed, according to the stats office.

In presenting the data, František Palko, state secretary of the Economy Ministry, argued that a year-on-year drop in GDP by as much as 5 percent had been expected in the first quarter due to impacts of the Russian gas crisis - which affected Slovakia at the beginning of the year - and the decline in external demand for Slovakia's products.

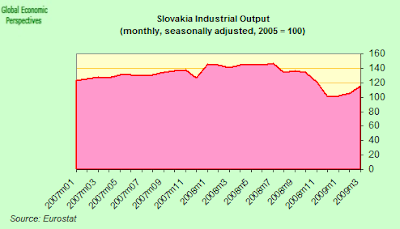

Certainly this decline is evident, since Slovak industrial output fell 22.9 percent in the first three months of the year, led unsurprisingly by the car industry, which had previously been the growth motor. In fact Slovak industrial output contracted at a slower inter-annual pace in March following a record plunge in February since European government incentives helped with car production and the electronics industry continued to expand. Output was down an annual 18 percent, making March the sixth consecutive month when production has contracted, a figure which compares with the revised 25.6 percent decline in February. Car production was down 30.1 percent year on year, compared with a 44 percent drop in the previous month.

The lions share of the fall in industrial output was due to a fall in demand for exports - Slovakia is a small, trade-dependent economy, and March exports decreased by 20,1 % compared with March 2008. Imports were down even more, by 23,1 %, and as a result the trade balance was in surplus (EUR 81,9 million). Over the first three months, as compared with the corresponding period last year, total goods exports were down by 28,6 % and total goods imports by 28,2 %. The quarterly trade balance registered a deficit of EUR 51,2 million (up by EUR 45,6 million compared with the same period in 2008).

Inflation Heading To Zero

The net result of the collapse in demand is an increase in the output gap and strong downward price pressure - in particular since as a member of the eurozone Slovakia no longer has its own currency to devalue. So it is hardly surprising to find the country's EU harmonized annual inflation rate falling back to 1.4 percent in April, its lowest level since August 2007, and down from 1.8 percent in March. Month on month, prices fell by 0.1 percent following a 0.3 percent decline in March. Indeed Slovakia is on the threshold of negative year on year inflation since consumer price indexes (both the general index and the core one) have actually been flat now since the start of the year (see chart below).

Indeed Slovakia is on the threshold of negative year on year inflation since consumer price indexes (both the general index and the core one) have actually been flat now since the start of the year (see chart below).

Waning demand is also leading companies to cut back on their workforces, pushing the March unemployment rate to 10.33 percent, the highest in almost three years. The rate, which is the highest since June 2006, was up from from 9.72 percent in February, according to the Bratislava based National Labor Office. The number of unemployed available for work in the country of 5.4 million people increased to 273,779 from 257,564. The unemployment rate has now been rising steadily from a record-low of 7.36 percent achieved in August last year. The EU harmonised rate published by Eurostat was up at 10.5% in March, from 10% in February. Despite all the talk of Slovakia having a "fexible" labour market, 7.36% is still a very high rate of employment to run when the economy is experiencing a massive boom, so it will be very interesting to see the actual rate of downward movement in wages (and prices) as the recession moves forward (another kind of "stress testing").

Despite all the talk of Slovakia having a "fexible" labour market, 7.36% is still a very high rate of employment to run when the economy is experiencing a massive boom, so it will be very interesting to see the actual rate of downward movement in wages (and prices) as the recession moves forward (another kind of "stress testing").

Pressure On Public Finances

Slovakia’s central budget deficit widened to 347.4 million euros at the end of April as the economic slowdown cut into tax revenue, according to the Finance Ministry. Revenue for the first four months of the year was 3.32 billion euros, lower than expenditure which amounted to 3.67 billion euros. The shortfall compares with a 204.6 million-euro difference in March and a surplus of 257 million euros at the end of April 2008. Slovakia originally targeted a central government budget deficit of 1 billion euros in 2009, or a shortfall of 2.1 percent of gross domestic product.

The Finance Ministry now estimates tax revenue will be about 1 billion euros short of the original projection, which was based on an expectation for GDP growth of 2.4 percent this year. The central bank now forecasts the economy will shrink 2.4 percent.

In 2008, the general government deficit increased to around 2.25% of GDP. The better-than expected budget outcome was the result of a number of the revenue-increasing measures (e.g. broadening of the corporate and personal income tax base, increase in the maximum ceiling on social contributions), which offset the revenue shortfall due to the deteriorating economic situation.

The 2009 general government deficit is forecast by the EU Commission to increase to 4.75% of GDP. On the revenue side, the anti-crisis packages include measures such as a temporary increase in the tax-free part of income from €3,435 to €4,027, an in-work benefit for low-income employees (negative income tax), as well as a decrease in social contributions for mandatorily insured self-employed. On the expenditure side, the bulk of the measures with budgetary impact are related to the subsidies for R&D activities, for programmes aiming at increasing energy efficiency and supporting existing or newly established SMEs as well as for the Slovak cargo and railway company.

The EU Commission expect the general government deficit to rise to 5½% of GDP in 2010, with the debt-to-GDP ratio increasing from 27.5% of GDP in 2008 to some 36% in 2010. Despite the deficit in excess of 3% of GDP, gross public debt is still very low, and ratings agency Standard & Poors were generally pretty positive in their most recent Slovakia outlook. They did however see two significant challenges lying ahead for Slovakia.

1) Firstly the rather obvious point that here is an increasing risk to the economy from Slovakia's high exposure to the auto sector.

2) And secondly, the rather more important point that since conversion to the euro was undertaken when the Slovak Koruna was trading at a short term peak - the government were using currency appreciation to soak up inflation and stay withing the Maastricht euro limits (see this post here) - Slovak exports are now somewhat penalised compared with those coming from some of their neighbours (the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary) - in terms of competitiveness, since while they were also using currency appreciation as an anti inflation posture during the height of the commodities surge, they have since been able to "correct" and allow their currencies to devalue. Personally I can't stress too strongly how important an issue I think this is.

The Slovak economy is very open, and indeed has become impressively more so in recent years. It is in fact the third most open economy in the EU after Luxembourg and Malta, according to Eurostat data (in the sense of a “small open economy”). In terms of trade in goods, Slovakia is even the most open economy in the EU. This situation in part reflects the country's small size - Slovak GDP represents only 0.6% of eurozone GDP, or some 2.4% of German GDP. Given Slovakia is so small and so open, a high proportion of domestic demand will now be met by imports from “cheaper” neighbours (notably Hungary and Poland). So Slovakian growth will have to rely more on investments in productive capacity and exports.

As I said above in this sense a shift in emphaisis is called for, since the economy is incredibly vulnerable to the automotive sector, and this in a situation where European car sales have slumpled, is, as weak can see, a lethal flaw. In fact the situation has been made worse by the recent wave of government-backed incentives, since they have only exacerbated the slump in demand for luxury models - like the Cayenne, the Audi Q7 and the Volkswagen-brand Touareg SUVs - which are over-represented in the Slovak sector ((in contrast, theCzech car industry is strongly profiting from car scrapping subsidies). These subsidies together with accompanying environmental incentives have shifted Europe’s shrinking car demand toward smaller and more fuel-efficient models, and hence global No.1 luxury carmaker Bayerische Motoren Werke AG’s registrations dropped by almost one-third in April (to 55,633) even as the German market as a whole expanded 19 percent. Daimler recorded a 26 percent sales decline to 60,214 cars, led by its Mercedes luxury brand.

The Slovak government has been having some success in diversifying the economy, for instance by attracting Sony and Samsung production facilities. Production of cars was down 30.1 percent in March, while output in the electronics industry rose an annual 50.3 percent.

More worryingly, the amount of foreign-investment pledged to Slovakia slumped 92 percent in the first quarter of the year as the global slowdown prompted companies to delay expansion. The only two projects brokered by the state SARIO investment agency in the first three months represent a total investment of 8 million euros, with the potential to create 220 jobs, according to spokeswoman Jana Murinova. In the same period last year, the agency negotiated nine projects worth 103 million euros and creating 1,455 jobs.

Slovakia adopted the euro last January, is now feeling the pressure of price competitiveness from neighbours who have retained an autonomous capacity to devalue their currency as investors as scale back expansion plans during the slowdown. During 2008 Slovakia attracted investment projects worth 538 million euros, less than a half of the 2007 total of 1.28 billion euros.

The Slovak case raises important questions, not least about the rigid application of the Maastricht criteria in a situation where they may not only have lost much of their original relevance, but even where they may lead to distortions - as in the Slovak case - which may mean a painful period of internal wage and price deflation is necessary to overcome the loss of competitiveness produced by entering the common currency at an unrealistically high parity .

Slovakia may now face a difficult period (like Portugal - see this post) of internal price adjustment having entered the euro at too high a rate. The openness of the economy will require more price and wage flexibility. Slovakia joined EMU with a relative strong exchange rate. Currencies of neighbouring countries have been depreciating significantly against the euro. So we are seeing strong deflationary pressures, and average industrial wages fell an annual 0.6 percent in March, following a 1.9 percent fall in February. In nominal terms, average monthly wages rose to 718 euros from 687 euros in February. However, for now these are nowhere near on the same scale as, for example, the impact of the drop in sterling on Ireland.

On a side issue Slovakia issued a 2 billion euro, 2015-dated bond yesterday at 170 basis points over mid swaps. So this can give you some idea what new eurozone members can expect in the future, somewhere up there in the spreads with Greece and Ireland. Slovakia is rated A1 by Moody's Investors Service, A+ by Standard & Poor's Corp. and A+ by Fitch Ratings.

So, while Hungary is still the worst performer among CEE EU member economies the two recent members of the Eurozone - Slovenia and Slovakia - are doing worse than anyone would have imagined, and this should lead to some serious questions being asked in Brussels and Frankfurt. Why is it that, for example, participants in a crisis racked economy like Latvia (whose economy is contracting at an 18% annual rate, and whose bankers and politicians are moving heaven and earth to try to scrape through the qualifying hurdle for eurozone membership) are still feeling better than many economic agents in the Eastern two countries who have actually managed to access the zone according to the latest reading of the EU Economic Sentiment Index. Eurozone membership is not a one way street, far from it. So what are the benefits, and what are the dangers, and how do we optimise the membership process?

References

Portugal Sustains - what are the lessons of Portugal's membership of the Eurozone (12 January 2009)

Slovakia’s Euro Membership Bid (April 21 2008)

Let The East Into The Eurozone Now! (22 February 2009)